SREI and the Pattern India Can No Longer Ignore: Paper Tigers and Public Losses

Let us ask ourselves a few questions: Why are banks in India always mired in controversies? Why are the regulators turning a blind eye to the activities of these institutions ? Were there any earlier signs to identify these scenarios which the banks and auditors could have ignored ? Who ultimately pays for these failures ?

Earlier this month, Punjab National Bank, India’s third-largest public sector bank, accused the former promoters of SREI Equipment Finance Ltd. and SREI Infrastructure Finance Ltd. of committing loan-related fraud. The disclosure comes nearly four years after the RBI initiated insolvency proceedings against the SREI Group, raising serious questions about delays in fraud recognition, regulatory oversight, and accountability within India’s public sector banking system. The amount reported by the bank is just over ₹2,434crore. PNB stated that the classification of these accounts as “fraud” is based on findings from a forensic audit. However, the SREI Group has challenged the forensic audit, arguing that the matter is under judicial consideration.

Can these frauds be detected by the RBI?

Former RBI adviser Ashok Nag pointed out that the Reserve Bank of India issued updated fraud-risk management and early-warning guidelines in 2024, replacing the earlier 2016 framework. These revised norms require banks to implement Early Warning Systems (EWS), use data-analytics-based monitoring, and ensure prompt reporting of suspected frauds. Given that the SREI accounts involved were large exposures well in excess of ₹1,000 crore, and that the RBI already tracks such borrowings through its Central Repository of Information on Large Credits (CRILC), the nearly two-year delay after resolution in formally classifying and reporting the accounts as fraud raises serious concerns about the effectiveness of PNB’s internal controls and compliance mechanisms.

The significance of such delays is also evident from the Vijay Mallya–Kingfisher Airlines debt crisis, where over ₹9,000 crore was lent by an SBI-led 17-bank consortium despite clear stress signals such as mounting losses, unpaid salaries, and grounded aircraft as early as 2010–11. Banks continued lending and restructuring even as debt ballooned to ₹5,665–7,000 crore, culminating in the airline’s shutdown in 2012 and Mallya being declared a willful defaulter. This case highlighted weaknesses in consortium lending, early-warning detection, and due diligence, ultimately contributing to India’s NPA reforms.

A similar pattern can be seen in the case of Yes Bank, where founder Rana Kapoor’s aggressive lending practices concealed NPAs through improper classifications and undisclosed bad loans. These hidden exposures eroded the bank’s capital without timely alerts, leading to RBI intervention and the eventual takeover in 2020. Another example is Dewan Housing Finance (DHFL), which misled a 17-bank consortium led by Union Bank for ₹35,000 crore through shell companies, fake appraisals, and phantom branches. These cases collectively underline a recurring issue: large loans sanctioned without proper safeguards, coupled with delayed fraud recognition, create systemic risks that often end up being borne by taxpayers.

Paper Tigers: Weak Implementation of Strong Regulations

Of what use are the regulations and fail-safes when they are not enforced?

The panel also raised critical concerns about regulatory effectiveness, questioning why RBI supervision failed to trigger earlier public disclosure, why forensic audit findings did not result in a faster classification of the accounts as fraud, and whether existing regulatory systems, despite being comprehensive and well-designed on paper, are actually being followed in practice. As Mr. Ashok Nag observed, while the regulatory framework is robust, the real weakness appears to lie in inconsistent and delayed implementation.

What truly vexes a well-informed citizen, however, is the recurring failure of banks, particularly in the public sector, to conduct thorough due diligence while sanctioning large loans. A brief look at the situation shows an industry-wide rot where regulations are treated merely as suggestions, and regulators are nothing more than paper tigers acting only after the incident has taken place.

What was the reason for default?

As Economist Mitali Nikore pointed out, there are deeper systemic issues:

Infrastructure finance companies inherently deal with large loan sizes, but:

- There were no effective caps on debt accumulation

- Boards failed to demand credible debt management plans

- SREI accumulated ₹32,000–35,000 crore in debt without sufficient safeguards

Sadly, the issue goes beyond one company and reflects poor governance across infrastructure lending.

Accountability: Who Pays the Price?

PNB has clarified that it has already made full provisions for the ₹2,434 crore exposure, meaning the bank has set aside capital to absorb the loss. But this raises an uncomfortable truth that public sector banks are ultimately backed by taxpayers, while legal and financial consequences for promoters often lag behind the detection of the fraud, leaving the bank and, ultimately, taxpayers to absorb the losses. The discussion echoed memories of India’s biggest banking scandal, the Nirav Modi, Mehul Choksi fraud, where PNB lost over ₹14,000 crore due to internal control failures.

Impact on Taxpayers and Depositors

Provisioning shields the bank, but taxpayers ultimately bear the indirect cost, from reduced lending capacity to funds that could have supported genuine businesses being lost to fraud, as Ms. Nikore pointed out.

Beyond the Perpetrator: What India’s Banking Frauds Reveal

This case underlines several uncomfortable realities:

- Legacy banking frauds take years to surface

- Strong regulations do not guarantee strong enforcement

- Accountability often stops short of regulators and senior bank officials

- The burden of failure ultimately falls on taxpayers, highlighting the cost of weak enforcement and delayed accountability.

When Regulators Fail: Global Lessons from Major Loan Frauds

India is not alone, global banking systems have also faced loan-related crises with far-reaching economic consequences

- Subprime Mortgage Lending Crisis (2007–2009)

The Subprime Mortgage Crisis of 2007–2009 was triggered by banks issuing high-risk housing loans to unqualified borrowers using teaser interest rates, no-documentation or NINJA (No Income, No Job, No Asset) loans, and falsified income statements. These loans were sanctioned on the assumption that rising property prices would offset defaults. When the housing market collapsed, the crisis resulted in an estimated $14 trillion loss in U.S. household wealth, 8.7 million job losses, and a 4.3% contraction in GDP, with the impact spreading globally through interconnected banking systems.

- Ireland Banking & Property Loan Crisis (2008–2010)

Ireland’s banking crisis between 2008 and 2010 was driven by excessive property lending of nearly €440 billion, fueled by low eurozone interest rates and weak regulatory oversight. Banks such as the Anglo-Irish Bank relied heavily on short-term foreign borrowings to finance real estate developers using inflated collateral valuations. When property prices declined by 50–70%, the banking system collapsed, forcing the government to inject €64 billion into the sector, pushing public debt to nearly 120% of GDP, and triggering political upheaval and large-scale emigration.

- Spain Cajas Real Estate Loan Collapse (2009–2012)

Spain’s regional savings banks, known as Cajas, extended more than €300 billion in property and developer loans during the construction boom between 2009 and 2012. Lending decisions were often based on inflated valuations, politically influenced appointments, and connected-party transactions, with limited independent oversight. Weak supervision by the Bank of Spain allowed governance failures, cronyism, and undisclosed losses to persist, ultimately forcing Spain to seek a European banking bailout as multiple institutions became insolvent.

- Mozambique “Tuna Bonds” Loan Fraud (2013–2016)

Between 2013 and 2016, Mozambique raised $2 billion in secret sovereign-guaranteed loans through arrangements involving Credit Suisse and VTB Bank for maritime security and tuna fishing projects. Three state-owned companies Ematum, Proindicus, and MAM secured the loans by misrepresenting project viability to investors. Investigations later revealed that over $200 million was paid in bribes and kickbacks, including more than $7 million received by former Finance Minister Manuel Chang, while banks ignored warning signs such as fees exceeding 12%. The undisclosed debt amounted to nearly 12% of Mozambique’s GDP, leading to default, austerity measures, civil unrest, and a sharp loss of investor confidence in emerging markets.

A Persistent Institutional Failure Across Political Eras

While this fraud is unrelated to past scandals, it reinforces a persistent concern:

“India’s public sector banks continue to struggle with risk management despite repeated crises and reforms.”

India’s banking fraud history shows that while political leadership has changed since Independence, systemic weaknesses in governance, accountability, and risk management, especially in public sector banks, have remained a persistent challenge.

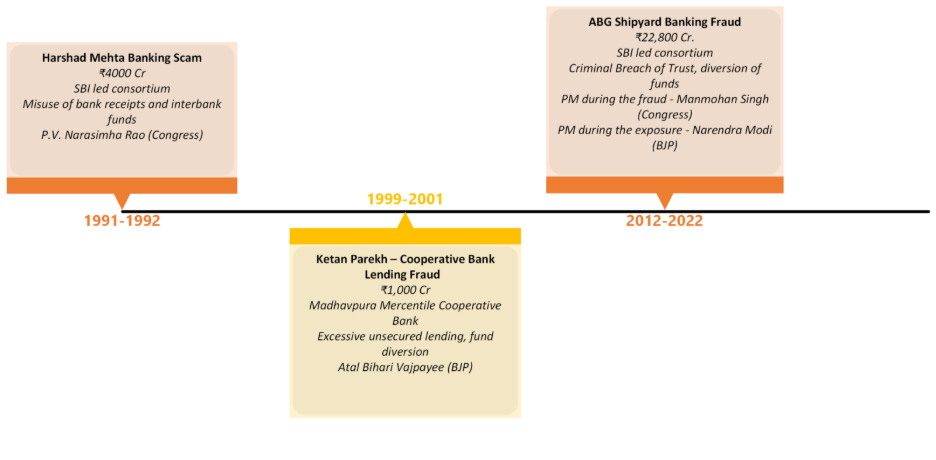

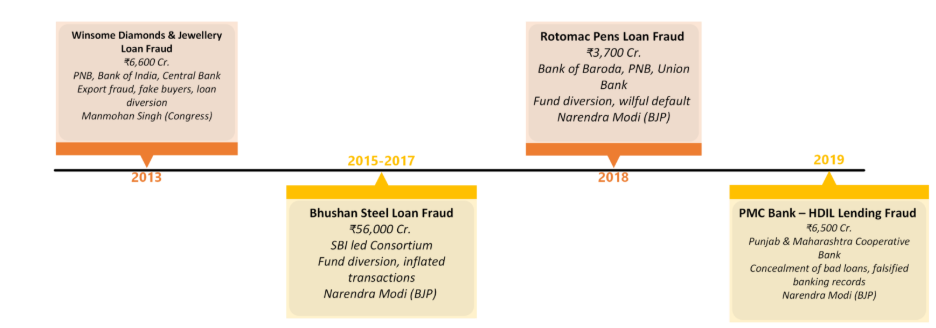

We have made a timeline of popular lending frauds committed by individuals and institutions in India over the years, it also includes the amount of exposure before recovery, the lending banks and the political party during whose reign the fraud took place in. The public has sometimes speculated possible political influence in certain cases, given the complexity of these frauds and the multiple layers of checks that were bypassed. However, in the absence of conclusive evidence, these remain unverified claims. However, in the absence of conclusive evidence, such claims remain only speculative at best. A few points to remember while going through this list are:

- Frauds occur across all governments; banking frauds are institutional failures, not election-cycle events.

- Most frauds are detected years after they occur, often under a different government.

- Public sector banks dominate lending while taxpayers bear losses.

- Post-2016 reforms, such as the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, Asset Quality Review and forensic audits, increased detection, and not necessarily fraud creation.

Conclusion: A Persistent Challenge

India’s banking sector continues to struggle with governance, risk management, and regulatory oversight, particularly in public sector banks. From Harshad Mehta to SREI, PMC–HDIL, and Kingfisher, large loans sanctioned without proper due diligence and delayed fraud detection have repeatedly left taxpayers footing the bill. Despite reforms like the IBC, Asset Quality Reviews, and RBI’s updated early-warning framework, enforcement gaps and weak accountability allow perpetrators to bypass safeguards.

Greater accountability at every level, including bank officials, auditors, and regulators, is crucial to prevent repeated banking failures. When ordinary citizens ask questions, demand transparency, and insist on timely disclosures, it pressures institutions to follow rules rigorously and act responsibly. Public scrutiny can complement regulatory frameworks, ensuring that reforms are enforced in practice, not just on paper, and that the burden of fraud does not fall on taxpayers.